We suggested recently that it might be a good time for you to take a long hard look at your organisation’s bonus scheme. Instead of motivating, engaging and rewarding staff for great performance and accountability, the bonus culture can get in the way, encouraging a silo mentality that undermines business success.

Evidence collected from our director clients indicate that they’re in the process of re-structuring bonuses so that the emphasis shifts from individual to team performance. This can be further demonstrated by the following case study sent to us by a former client who’s kindly given us permission to publish it:

Bonus Culture Case Study

We have quite a high proportion of cases where time costs exceed billable fees, so we created a bonus scheme based on a percentage of fee income above a base level. The aim was to focus people’s minds on dealing with loss-making cases quickly, so they could spend more time on cases where the time can be successfully billed.

Did it work? Only sort of: fees and profitability went up, which is great and bonus payouts were significant – up to 20% of income for the staff, and far more than I expected – also good. But the staff aren’t the ones driving it – I am. The one big step we were hoping they would take for themselves has not happened. If we had not bothered with the bonus scheme, there would have been more profit for me to take home! It seems that the link between work done today and payout of the bonus twice a year is just too remote for people to make the connection between today’s activities and actually seeing money in the bank.

However, the bonus scheme for my staff was a major success compared to the rest of the firm. The gross profit improvement target has been missed for three years, and now talk of a bonus scheme is just scoffed at by the staff; they know they have put in effort and now consider they are going unrewarded.

My lesson from bonus schemes is that:

- It has to be designed so there is some sort of payout;

- Cash is not everything and enjoyment of work is often more important, though some employees don’t recognise it until they have left a good employer for a higher salary;

- A bonus scheme does put pressure on people to perform at a higher standard and they don’t like the constant pressure. I think my staff liked the fact that they got a proportion of the increased fees as a reward for their hard work but I was mistaken to think they would reform their behaviours and become more time conscious on the loss-making jobs;

- The idea that staff will police each other is a fallacy – they don’t. They just grumble about those they consider to be ‘non-performers’ and don’t even bring their concerns and grumbles to management;

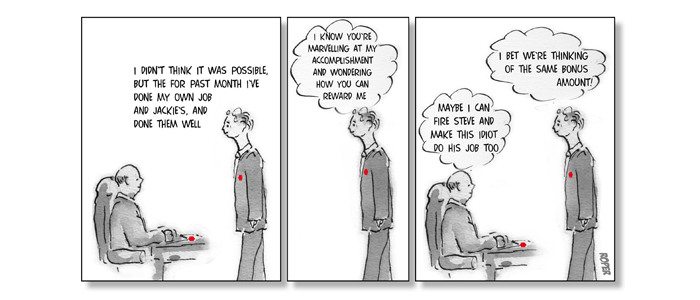

- A global bonus scheme is an avoidance of responsibility by management; they don’t have to think about proper reward for those that deserve it. They aren’t facing up to their responsibility to deal with poor performers.

I don’t resent what they got out of it at all – I have willingly paid out discretionary bonuses in the past. It’s just that, with the new scheme, I totally misjudged their ability to self-regulate their activities. Because the bonus scheme was pro-rated against salary, everyone got the same ‘pence in the £’. If I had been able to use my discretion everyone would have got something but some wouldn’t have got quite so much.

However, my staff were very grateful to have been put on a different scheme to the rest of the firm and there was an unexpected by-product. When the payouts happened, I got a great ‘feel-good factor’ from the few that actually came to me to say ‘thank you’. So perhaps it did work – I got an increased profit and that little moment of being made to feel really good!

So what’s the take-away from this? It’s that although you can engineer the best bonus scheme in the world, it’s still not a replacement for effective hands-on management (though it’s too often used that way).