Do you find yourself feeling that you can’t trust people in your business to do what you want them to do? It’s a common complaint among business leaders, and their usual assumption is that there is something wrong with the people they employ. Among the knee-jerk reactions to this thought are: tightening up on performance management (though usually with the complaint that “I shouldn’t have to”); issuing warnings; reorganising the management structure; and, finally, even firing someone and recruiting a new person.

It’s all very stressful, disruptive and damaging to the culture of responsibility, trust and partnership that most people would say is their ideal working environment.

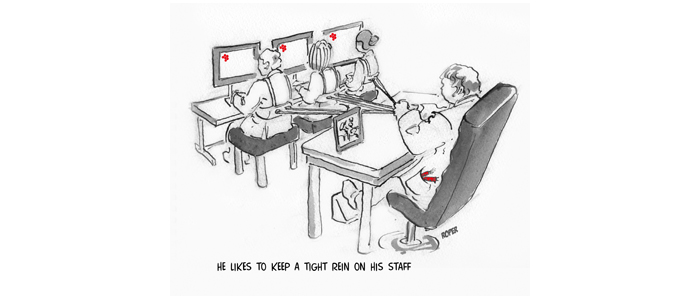

So what’s the alternative? Well, you might not like this, but the answer very often isn’t in ‘them’ – it’s in you. If your prevailing assumption is that only you really know how to run your operation (you have to be honest here), and other people need to be watched like a hawk if they are not to let you down, then guess what: that’s what will happen.

It’s called the ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’, and fascinating experiments have been done in the area of human behaviour to show that if the ‘boss’ has certain negative assumptions about the ‘employees’, they will quickly begin to live up (or down) to those assumptions.

A famous example includes a study where teachers were told arbitrarily that random students were ‘going to blossom’; those random students actually ended the year with significantly greater improvements. Conversely, there have been studies where teachers were told to expect negative grades from certain randomly selected students, who duly proceeded to perform in line with the teacher’s expectations.

“But”, you might say, “how can I stop myself thinking what I think? I do my best to hide it, but people seem consistently to let me down, whatever I do or say”.

It’s not easy, but it starts with examining very careful what you are really thinking in your heart of hearts. Not the politically correct, enlightened things you would say in public, but the things you say to yourself (or to your nearest and dearest) when you are angry, frustrated, or just plain despairing of ever getting the support and partnership you need from your staff.

If you’d like to try, follow these steps:

- Identify the situation.

Describe the situation or behaviour that triggered your negative mood. When did it start? What happened? What else was happening at the time? Be as specific as possible.

- Identify automatic thoughts – your parrot.

Make a list of all the automatic thoughts you had in response to the situation. This is the ‘parrot on your shoulder’, your inner dialogue, coming up with perceptions and trying to find meaning in the situation to explain your emotional reaction. Try to catch your own mind talking – what’s it saying?

Some of us blame others: “they’re out to get me”, “he’s lazy”, as a first reaction. Underlying this though may be an opinion about yourself which disempowers you: “why can’t I come up with a solution?”, “what’s wrong with me, that I can’t get through to him?”, “I’m no good at motivating people”.

- Analyse your mood in detail – your emotional response.

Describe how you felt in the situation and how you’re feeling now. Examples might include: angry, upset, frustrated, scared, anxious, depressed, betrayed or embarrassed.

- Describe the action you took.

Describe how a combination of your thoughts and your emotions caused you to act in the situation: “I felt shaky and walked away”, “I got angry and shouted at her”.

- Find objective supportive evidence.

Now go back and challenge the conclusions you came to: write down any evidence you can find that supports the automatic thoughts you listed in Step 2. For “I’m no good at motivating people”, you might write down, “my staff don’t do what I want them to do”, and “no-one emptied the bins and a client came in on Monday morning to a mess”. Come up with any and all thoughts you are having about the situation.

- Find objective contradictory evidence.

Now look rationally at your automatic thoughts and write down objective evidence that contradicts the thought. Consider other people’s perspectives as well – ask them, if necessary. Write down your new perspective. You might list successes you have had, good feedback you’ve received and people who respect and like you: “I’m great at organising my Saturday football team”, “everyone says I’m a really inspiring school governor”, and so on.

- Identify fair and balanced thoughts.

Look again at the thoughts you wrote down in Steps 5 & 6. Take a balanced view of the situation and write down your conclusions. So: “OK, my staff don’t do what I want them to do, but I’ve clearly got the skills to motivate people – the football team voted me in as captain and I know I’m a good school governor”.

- Monitor your present mood.

Assess your mood now. What’s the difference between the way you feel about, your perceptions of, your mates on the football team and the way you regard your staff? This difference is what’s making it hard for you to motivate your staff.

With very rare exceptions, nobody comes to work to be lazy and do a bad job. Everybody is just doing their best – they may need a bit more information or guidance from you, but that’s your job! Recognise that if people are showing up to you as lazy and irresponsible, then that’s probably what you are unconsciously causing to happen. Work hard on changing that underlying script, and you’ll be amazed at how people’s natural enthusiasm and responsibility emerges. Listen to them and start asking what they need from you. And if they say they need more time, objectives and guidance, then rather than saying “I shouldn’t have to”, say to yourself, “great, that’s my job”, and give them the time they need, to be able to give you what you need.